By Jonathan Margolis, Thirsk

© Time December 14, 1992

With the hushed solemnity of Pilgrims before a holy relic, four American tourists gaze at an unoccupied bar table in an English pub. “Will you just look at that” one exclaims. The two men in the group begin to take photographs, not of their wives with the table, but of the table itself.

For the millions around the world who are devotees of James Herriot, the British veterinarian and author, this incident, recalled by Liz Hopwood, the pub landlady, will make sense. For those who have not been touched by Herriot’s folksy writings about life as a vet in rural northern England, it may take some explanation.

The table, you see, in the saloon of the Kings Arms in the village of Askrigg, North Yorkshire, was once briefly glimpsed in the BBC-TV adaption of Herriot’s All Creatures Great and Small. James Herriot has never supped a pint of bitter while sitting at it, nor has he ever frequented the Kings Arms. Indeed, strictly speaking, James Herriot does not even exist–it is a pen name for one James Alfred Wight, a real, though now retired, vet who lives and writes outside a town called Thirsk in a quite different part of Yorkshire, about 50km to the east of Askrigg.

Yet such is the adulation for what Wight calls his “little cat-and-dog stories” that even a piece of furniture distantly, and with some effort of imagination, connected with him can elicit acts of homage from admirers. In literary terms, Herriot’s writing may be as homely and bucolic as an English village tea shop, but make no mistake, he is a major author. His latest book, Every Living Thing, which takes the story of Herriot/Wight’s family and practice into the ’50s, came out in Britain in October and went straight into the Top 10 of the British best-seller list. In the U.S. it has been high on the New York Times best-seller list for three months, and the publisher has rushed 865,000 hard-cover volumes into the marketplace with all the anticipatory fervor of a cow in clover.

The figure is more remarkable given that Herriot is 76, has long since retired as a vet and has not published in a decade. But the pent-up demand by readers for an unchallenging, uplifting breath of fresh–if occasionally farmyard-scented–air from Yorkshire seems greater than ever. If all 865,000 copies of the new book are sold in the run-up to Christmas, Herriot will be on the way to dwarfing even his previous massive sales. Twenty years ago, his first U.S. book, All Creatures Great and Small, sold 206,000 in hard-cover and 4.1 million in paperback. Later books all managed around half a million in hard-cover and several million in mass-market editions. All Creatures still holds the record as the most popular Reader’s Digest condensed book in that series’ 42-year history.

If unpretentiousness could be measured like book sales, Alf Wight, possibly the least likely popular idol of the late 20th century, would also break records. Meet him for lunch in his hometown, and you are made to feel you have done him a kindness by traveling to Yorkshire, when it is he who has granted a rare interview. Publicity he can take or leave, and for 10 years has chosen to leave it: “I’m one of those lucky people who don’t need anything,” he says in the soft accent of his native Scotland. Wight, whose mother was a singer and whose father played the piano in a movie theater, came to Yorkshire fresh from Glasgow’s veterinary college in the ’30s in response to a small ad for an assistant vet.

He never left the county–or the country–despite urgings in recent years by tax accountants to depart for an offshore tax haven. Once he and his wife Joan were taken bodily to the island of Jersey by a financial adviser determined to prove his point, but even with marginal income tax rates in mainland Britain at the time running as high as 83%, Wight calculated that he could live comfortably in Yorkshire on the small percentage of his books-boosted earnings the taxman allowed him to keep. He stayed in practice in the North Country, combining a winning barnside manner–only two dog bites in a 50-year career–with writing in front of the television set in the evenings. Wight is a dapper man, courteous, a little frail but by no means in his anecdotage. He has a still unexhausted mental filing system of sentimental animal stories and homespun philosophy.

“There was no last animal I treated,” he says of his retirement. “When young farm lads started to help me over the gate into a field or a pigpen, to make sure the old fellow wouldn’t fall, I started to consider retiring. The great momnet was one day when I was stitching up a cow’s teats–they often get cut, you know–and my glasses were sliding down my nose. Suddenly I thought, Wight, you’re too old for this. But it was a gradual transition. I just did less and less. It must be terrible to have a job you very much love chopped off.”

As he eats in a hotel restaurant just renamed Herriot’s–an honor this local hero modestly fails to notice–he greets a succession of old friends with a smile and a nod. Even the odd sign of commercial exploitation of his name fails to rouse his ire. A cafe called Darrowby Fayre–after the name he gave his town in his books–has opened in Thirsk’s cobbled marketplace. Wight explains that he doesn’t mind, but “the copyright is protected by some very fearsome American film-industry lawyers. They’d better watch out.”

The fact that James Herriot of the imaginary Darrowby is really Alf Wight of Thirsk is no longer a secret. A quaint journalistic convention of not identifying him or his location grew up early in his writing career, when he was still practicing as a vet and would tell reporters who tracked him down, “If a farmer calls me to a sick animal, he couldn’t care less if I were George Bernard Shaw.” Tourists nevertheless found him, and now routinely visit both his real hometown and the TV setting over in the Yorkshire Dales. In the ’70s, at the height of the first wave of Herriot mania, 40,000 fans, the majority American but some from as far afield as Japan and New Zealand, were reputedly coming to Thirsk each summer, as thrilled at finding the real Herriot as they might be by running into Sherlock Holmes outside 221B Baker Street. With books under their arm for signature, they lined up at Wight’s surgery until, after years of book signing, the vet’s hand became almost unusable because of arthritis. “They can’t find my house now because I keep it very quiet where I live,” he says with relief, having moved to a quiet spot outside Thirsk.

Paradoxically, Herriot made the sumptous Yorkshire countryside better known in New York City and Yokohama than it was in the south of England, where until All Creatures Great and Small was shown on TV, some Londoners were still convinced that Yorkshire was a collage of dark statanic mills and bleak Bronte moorland. “I’ve been a godsend for little farmers, you know, doing bed-and-breakfasts for visitors,” Wight says, understating as ever. Herriot has brought an entire tourist industry to the Pennine uplands and valleys.

“I love writing about my job because I loved it, and it was a particularly interesting one when I was a young man. It was like holidays with pay to me. I think it was the fact that I liked it so much that made the writing just come out of me automatically. I was helped by having a verbatim memory of what happened years ago, even if I can’t remember what happened a couple of days ago. Years ago, farmers were uneducated and eccentric and said funny things, and we ourselves were comparatively uneducated. We had no antibiotics, few drugs. A lot of time was spent pouring things down cows’ throats. The whole thing added up to a lot of laughs. There’s more science now, but not so many laughs.”

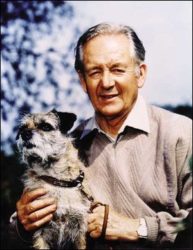

Wight in retirement is having the time of his life. He walks his Border Terrier, Bodie; goes out for dinner with friends; spends time with his daughter, a physician, and his son, a vet. He drives around the district in a scarlet Audi sports mode, incongrous perhaps for an elderly retired vet, but Herriot readers will recall that he always enjoyed charging through the dramatic Yorkshire countryside in red-blooded cars. He also still sees one of his old partners, the colorful “Siegfried.”

“He dropped in this morning,” says Wight. “Typical Siegfried, he’s 81 and was carrying a bottle of champagne he wanted me to test. Tristan, sadly, to whom I was very close, died three years ago.” Wight refers to his friends by their fictional names, the result of years of trying to oblige fans caught up in the Darrowby theme-park version of Yorkshire. “There were times,” Wight recalls, “when Siegfried was a bit taken aback by the way he was portrayed. He once said that the first book was a test of our friendship. Tristan, on the other hand, didn’t give a damn.”

The story of Herriot, author (as opposed to the perfectly satisfactory story of Wight, country vet), is a stirring one for anyone in middle age who believes he might write a book one day. “For years I used to bore my wife over lunch with stories about funny incidents. The words ‘My book,’ as in ‘I’ll put that in it one day,’ became a sort of running joke. Eventually she said, ‘Look, I don’t want to offend you, but you’ve been saying that for 25 years. If you were going to write a book, you’d have done it. You’re never going to do it now. Old vets of 50 don’t write books.’ So I purchased a lot of paper right then and started to write.”

Along with the paper, he bought several books of the “Teach Yourself to Write” variety but did not get very far with his early efforts–adventure stories and pieces about soccer, his passion. “I became a connoisseur of that nasty thud a manuscript makes when it comes through the letter box.” Even the first animal book, If Only They Could Talk, which inspired the London publisher Michael Joseph, was limping along in Britain with sales of around 1,500 before a copy made its way to Tom McCormack, then president of St. Martin’s Press in New York City.

“The title was awful for America,” McCormack recalls. He left it on a table, where his wife, then an editor at St. Martin’s, started reading it. But even though ‘she got me by the lapels and said, ‘You have got to read this book,'” McCormack remained unconvinced. “I told Mr. Herriot with a metaphorical cigar in my mouth to give me three chapters in which the hero gets the girl. He did, and they clanged like The Sound of Music. Believe it. Alf is an artist. He is immensely skillful.”

St. Martin’s combined If Only They Could Talk and It Shouldn’t Happen to a Vet in one volume. Wight’s daughter came up with the witty title Ill Creatures Great and Small, adapted from a line in the hymn All Things Bright and Beautiful, and McCormack adapted it back again by reverting from Ill to All. Soon McCormack was lunching Wight at the Connaught, one of the most expensive hotels in London. “I was crazed about this thing,” McCormack recalls. “I’ve never known anything as sharply, as unquestionably, as religiously as I knew this book was going to be a champ. Now he’s a global star, and I maintain he’ll be in print a hundred years from now.”

But whether the James Herriot story will ever be taken beyond this latest installment remains entirely within Wight’s gift. “I will write another book if I feel like it,” he says after some thought. One thing he has to think about is waiting–in the nicest possible way–for people to die. Dead people are notoriously less litigious than the living.

There is another proble, however. If the Herriot saga continues to mirror reality, the kindly sage of Darrowby will soon be taking on a literary agent and a phalanx of tough American lawyers, having lunch at the Connaught and tea at the Polo Lounge in Beverly Hills, California, and having more tourists than sick animals lining up outside his vet’s surgery. Wight knows better than anyone that if the Herriot series becomes a literary matrioshka doll, with a wordly success story and global fame nesting inside a simple tale of country people, it will lose the kernel of its charm.

And anyway, what would he call a new volume? It Shouldn’t Happen to a Multimillionaire?